Originally called Armistice Day, we celebrate Veteran’s Day on the 11th day of the 11th month to honor those who have served our country in the armed forces of the United States. In Scouting, we can be especially proud of the twelve Eagle Scouts who have earned the highest award for bravery and gallantry that the miltary services can bestow, The Congressional Medal of Honor.

1

Rear Admiral Eugene “Lucky” Fluckey was a United States Navy rear admiral who received the Medal of Honor and four Navy Crosses during his service as a submarine commander in World War II. Fluckey established himself as one of the greatest submarine skippers, credited with the most tonnage sunk by a U.S. Naval skipper during World War II: 17 ships including a carrier, cruiser, and frigate.

In one of the more unusual incidents in the war, Fluckey sent a landing party ashore to set demolition charges on a coastal railway line on Sakhalin Island (then part of Japan’s Karafuto Prefecture), destroying a 16-car train. This was the sole landing by U.S. military forces on the Japanese home islands during World War II. Fluckey ordered that this landing party be composed of crewmen from every division on his submarine. “He chose an eight-man team with no married men to blow up the train,” Captain Max Duncan said, who served as Torpedo Officer on the Barb during this time. “He also wanted former Boy Scouts because he thought they could find their way back.”

2

Lieutenant Colonel Aquilla James Dyess was a United States Marine Corps officer who was a posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life” at the head of his troops during World War II, in the Battle of Kwajalein, on Namur Island, Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands on February 2, 1944.

Lieutenant Colonel Aquilla James Dyess was a United States Marine Corps officer who was a posthumous recipient of the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life” at the head of his troops during World War II, in the Battle of Kwajalein, on Namur Island, Kwajalein Atoll, Marshall Islands on February 2, 1944.

On February 1, 1944, the day preceding Dyess’s death, six U.S. Marine snipers were on patrol on Namur Island where Japanese forces had taken up protected positions following the Battle of Kwajalein. The Marine patrol had inadvertently moved behind enemy lines, surrounded on three sides by Japanese forces, where they came under small arms fire from a concealed position. One of the Marines was killed instantly, and four of the remaining five Marines sustained injuries from the attack. One of the injured Marines, Cpl. Frank Pokrop, later recalled, “with no protection and heavy fire coming at us from a few feet away and dusk approaching, we were certain to be killed. All of a sudden Col. Dyess broke through on the right, braving the very heavy fire, and got all of us out of there.”

Lieutenant Colonel Dyess was killed the next day by a burst of enemy machine gun fire while standing on the parapet of an anti-tank trench directing a group of infantry in a flanking attack against the last Japanese position in the northern part of Namur Island. In this final assault, Dyess posted himself between the opposing lines and, exposed to fire from heavy automatic weapons, led his troops in the advance. Wherever the attack was slowed by heavier enemy fire, he quickly appeared and placed himself at the head of his men and inspired them to push forward.

3

Robert Edward Femoyer served in the U.S. Army Air Forces and is the only navigator awarded the Medal of Honor. On November 2, 1944, he was the navigator of a B-17 Flying Fortress on a bombing mission over Merseburg, Germany, his bomber was struck by three antiaircraft shells and he was wounded. He was in pain and had significant blood loss, but refused morphine in order to keep his head clear while he continued to navigate the bomber for two and a half hours, changing course six times to avoid enemy antiaircraft fire. He remained alert though his pain was described as “almost beyond the realm of human endurance”. Once the airplane was in safe airspace over the English Channel, Femoyer finally agreed to an injection of morphine; but thirty minutes after landing he died of wounds. His actions saved the lives of the entire crew. For his actions during this mission, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

Robert Edward Femoyer served in the U.S. Army Air Forces and is the only navigator awarded the Medal of Honor. On November 2, 1944, he was the navigator of a B-17 Flying Fortress on a bombing mission over Merseburg, Germany, his bomber was struck by three antiaircraft shells and he was wounded. He was in pain and had significant blood loss, but refused morphine in order to keep his head clear while he continued to navigate the bomber for two and a half hours, changing course six times to avoid enemy antiaircraft fire. He remained alert though his pain was described as “almost beyond the realm of human endurance”. Once the airplane was in safe airspace over the English Channel, Femoyer finally agreed to an injection of morphine; but thirty minutes after landing he died of wounds. His actions saved the lives of the entire crew. For his actions during this mission, he posthumously received the Medal of Honor.

4

Walter Joseph “Joe” Marm Jr. is a retired United States Army colonel and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Vietnam War. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. As a platoon leader in the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), 1st Lt. Marm demonstrated indomitable courage during a combat operation. His company was moving through the valley to relieve a friendly unit surrounded by an enemy force of estimated regimental size. 1st Lt. Marm led his platoon through withering fire until they were finally forced to take cover. Realizing that his platoon could not hold very long, and seeing four enemy soldiers moving into his position, he moved quickly under heavy fire and annihilated all 4. Then, seeing that his platoon was receiving intense fire from a concealed machine gun, he deliberately exposed himself to draw its fire. Thus locating its position, he attempted to destroy it with an antitank weapon. Although he inflicted casualties, the weapon did not silence the enemy fire. Quickly, disregarding the intense fire directed on him and his platoon, he charged 30 meters across open ground, and hurled grenades into the enemy position, killing some of the 8 insurgents manning it. Although severely wounded, when his grenades were expended, armed with only a rifle, he continued the momentum of his assault on the position and killed the remainder of the enemy. 1st Lt. Marm’s selfless actions reduced the fire on his platoon, broke the enemy assault, and rallied his unit to continue toward the accomplishment of this mission. 1st Lt. Marm’s gallantry on the battlefield and his extraordinary intrepidity at the risk of his life are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.

Walter Joseph “Joe” Marm Jr. is a retired United States Army colonel and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Vietnam War. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of life above and beyond the call of duty. As a platoon leader in the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), 1st Lt. Marm demonstrated indomitable courage during a combat operation. His company was moving through the valley to relieve a friendly unit surrounded by an enemy force of estimated regimental size. 1st Lt. Marm led his platoon through withering fire until they were finally forced to take cover. Realizing that his platoon could not hold very long, and seeing four enemy soldiers moving into his position, he moved quickly under heavy fire and annihilated all 4. Then, seeing that his platoon was receiving intense fire from a concealed machine gun, he deliberately exposed himself to draw its fire. Thus locating its position, he attempted to destroy it with an antitank weapon. Although he inflicted casualties, the weapon did not silence the enemy fire. Quickly, disregarding the intense fire directed on him and his platoon, he charged 30 meters across open ground, and hurled grenades into the enemy position, killing some of the 8 insurgents manning it. Although severely wounded, when his grenades were expended, armed with only a rifle, he continued the momentum of his assault on the position and killed the remainder of the enemy. 1st Lt. Marm’s selfless actions reduced the fire on his platoon, broke the enemy assault, and rallied his unit to continue toward the accomplishment of this mission. 1st Lt. Marm’s gallantry on the battlefield and his extraordinary intrepidity at the risk of his life are in the highest traditions of the U.S. Army and reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of his country.5

Mitchell Paige (Mihajlo Pejić) was an American-Serbian retired United States Marine Corps colonel who received the Medal of Honor during World War II.

On October 26, 1942, after thirty-three Marines in his machine gun platoon were killed or wounded defending a ridge during the Battle of Guadalcanal, Platoon Sergeant Paige made a desperate stand against Japanese troops after they had broken through the lines and killed or wounded all of the other Marines in his machine gun section. Platoon Sergeant Paige fired his machine gun until it was destroyed, then moved from gun to gun, keeping up a withering fire until he finally received reinforcements, singlehandedly stopping an entire Japanese regiment. He later led a bayonet charge that drove the Japanese back and prevented a breakthrough in American lines. While on Guadalcanal, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the field on December 19, 1942.

Mitchell Paige (Mihajlo Pejić) was an American-Serbian retired United States Marine Corps colonel who received the Medal of Honor during World War II.

On October 26, 1942, after thirty-three Marines in his machine gun platoon were killed or wounded defending a ridge during the Battle of Guadalcanal, Platoon Sergeant Paige made a desperate stand against Japanese troops after they had broken through the lines and killed or wounded all of the other Marines in his machine gun section. Platoon Sergeant Paige fired his machine gun until it was destroyed, then moved from gun to gun, keeping up a withering fire until he finally received reinforcements, singlehandedly stopping an entire Japanese regiment. He later led a bayonet charge that drove the Japanese back and prevented a breakthrough in American lines. While on Guadalcanal, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the field on December 19, 1942.6

Thomas Rolland Norris is a retired United States Navy SEAL and Distinguished Eagle Scout, who received the Medal of Honor for his ground rescue with the assistance of Petty Officer Third Class Nguyen Van Kiet of two downed aircrew members in Quảng Trị province during the Vietnam War on April 10–13, 1972. Norris was one of few remaining SEALs in Vietnam when Lieutenant Colonel Iceal Hambleton was shot down behind enemy lines. Aerial combat search and rescue operations failed, leading to the loss of five additional aircraft and the death of 11 or more airmen, two captured, and three more down and needing rescue. Norris was tasked with mounting a ground operation to recover Hambleton, Lieutenant Mark Clark, and Lieutenant Bruce Walker from behind enemy lines. Assisted by Vietnamese Sea Commando forces, he and Republic of Vietnam Navy Petty Officer Nguyen Van Kiet went more than 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) behind enemy lines and successfully rescued two of the downed American aviators. Walker was discovered and killed by the North Vietnamese Army. Though Norris at first rejected the honor, he was recognized with the Medal of Honor in 1975.

Thomas Rolland Norris is a retired United States Navy SEAL and Distinguished Eagle Scout, who received the Medal of Honor for his ground rescue with the assistance of Petty Officer Third Class Nguyen Van Kiet of two downed aircrew members in Quảng Trị province during the Vietnam War on April 10–13, 1972. Norris was one of few remaining SEALs in Vietnam when Lieutenant Colonel Iceal Hambleton was shot down behind enemy lines. Aerial combat search and rescue operations failed, leading to the loss of five additional aircraft and the death of 11 or more airmen, two captured, and three more down and needing rescue. Norris was tasked with mounting a ground operation to recover Hambleton, Lieutenant Mark Clark, and Lieutenant Bruce Walker from behind enemy lines. Assisted by Vietnamese Sea Commando forces, he and Republic of Vietnam Navy Petty Officer Nguyen Van Kiet went more than 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) behind enemy lines and successfully rescued two of the downed American aviators. Walker was discovered and killed by the North Vietnamese Army. Though Norris at first rejected the honor, he was recognized with the Medal of Honor in 1975.7

Arlo L. Olson was a United States Army officer and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in World War II. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. On October 13, 1943, when the drive across the Volturno River began, Capt. Olson and his company spearheaded the advance of the regiment through 30 miles of mountainous enemy territory in 13 days. Placing himself at the head of his men, Capt. Olson waded into the chest-deep water of the raging Volturno River and despite pointblank machine-gun fire aimed directly at him made his way to the opposite bank and threw 2 handgrenades into the gun position, killing the crew. When an enemy machinegun 150 yards distant opened fire on his company, Capt. Olson advanced upon the position in a slow, deliberate walk. Although 5 German soldiers threw handgrenades at him from a range of 5 yards, Capt. Olson dispatched them all, picked up a machine pistol and continued toward the enemy. Advancing to within 15 yards of the position he shot it out with the foe, killing 9 and seizing the post. Throughout the next 13 days Capt. Olson led combat patrols, acted as company No. 1 scout and maintained unbroken contact with the enemy. On October 27, 1943, Capt. Olson conducted a platoon in attack on a strongpoint, crawling to within 25 yards of the enemy and then charging the position. Despite continuous machinegun fire which barely missed him, Capt. Olson made his way to the gun and killed the crew with his pistol. When the men saw their leader make this desperate attack they followed him and overran the position. Continuing the advance, Capt. Olson led his company to the next objective at the summit of Monte San Nicola. Although the company to his right was forced to take cover from the furious automatic and small arms fire, which was directed upon him and his men with equal intensity, Capt. Olson waved his company into a skirmish line and despite the fire of a machinegun which singled him out as its sole target led the assault which drove the enemy away. While making a reconnaissance for defensive positions, Capt. Olson was fatally wounded. Ignoring his severe pain, this intrepid officer completed his reconnaissance, supervised the location of his men in the best defense positions, refused medical aid until all of his men had been cared for, and died as he was being carried down the mountain.

Arlo L. Olson was a United States Army officer and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in World War II. His citation reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty. On October 13, 1943, when the drive across the Volturno River began, Capt. Olson and his company spearheaded the advance of the regiment through 30 miles of mountainous enemy territory in 13 days. Placing himself at the head of his men, Capt. Olson waded into the chest-deep water of the raging Volturno River and despite pointblank machine-gun fire aimed directly at him made his way to the opposite bank and threw 2 handgrenades into the gun position, killing the crew. When an enemy machinegun 150 yards distant opened fire on his company, Capt. Olson advanced upon the position in a slow, deliberate walk. Although 5 German soldiers threw handgrenades at him from a range of 5 yards, Capt. Olson dispatched them all, picked up a machine pistol and continued toward the enemy. Advancing to within 15 yards of the position he shot it out with the foe, killing 9 and seizing the post. Throughout the next 13 days Capt. Olson led combat patrols, acted as company No. 1 scout and maintained unbroken contact with the enemy. On October 27, 1943, Capt. Olson conducted a platoon in attack on a strongpoint, crawling to within 25 yards of the enemy and then charging the position. Despite continuous machinegun fire which barely missed him, Capt. Olson made his way to the gun and killed the crew with his pistol. When the men saw their leader make this desperate attack they followed him and overran the position. Continuing the advance, Capt. Olson led his company to the next objective at the summit of Monte San Nicola. Although the company to his right was forced to take cover from the furious automatic and small arms fire, which was directed upon him and his men with equal intensity, Capt. Olson waved his company into a skirmish line and despite the fire of a machinegun which singled him out as its sole target led the assault which drove the enemy away. While making a reconnaissance for defensive positions, Capt. Olson was fatally wounded. Ignoring his severe pain, this intrepid officer completed his reconnaissance, supervised the location of his men in the best defense positions, refused medical aid until all of his men had been cared for, and died as he was being carried down the mountain.8

Captain Ben L. Salomon was serving at Saipan, in the Marianas Islands on July 7, 1944, as the Surgeon for the 2nd Battalion, 105th Infantry Regiment, 27th Infantry Division. The Regiment’s 1st and 2d Battalions were attacked by an overwhelming force estimated between 3,000 and 5,000 Japanese soldiers. It was one of the largest attacks attempted in the Pacific Theater during World War II. Although both units fought furiously, the enemy soon penetrated the Battalions’ combined perimeter and inflicted overwhelming casualties. In the first minutes of the attack, approximately 30 wounded soldiers walked, crawled, or were carried into Captain Salomon’s aid station, and the small tent soon filled with wounded men. As the perimeter began to be overrun, it became increasingly difficult for Captain Salomon to work on the wounded. He then saw a Japanese soldier bayoneting one of the wounded soldiers lying near the tent. Firing from a squatting position, Captain Salomon quickly killed the enemy soldier. Then, as he turned his attention back to the wounded, two more Japanese soldiers appeared in the front entrance of the tent. As these enemy soldiers were killed, four more crawled under the tent walls. Rushing them, Captain Salomon kicked the knife out of the hand of one, shot another, and bayoneted a third. Captain Salomon butted the fourth enemy soldier in the stomach and a wounded comrade then shot and killed the enemy soldier. Realizing the gravity of the situation, Captain Salomon ordered the wounded to make their way as best they could back to the regimental aid station, while he attempted to hold off the enemy until they were clear. Captain Salomon then grabbed a rifle from one of the wounded and rushed out of the tent. After four men were killed while manning a machine gun, Captain Salomon took control of it. When his body was later found, 98 dead enemy soldiers were piled in front of his position. Captain Salomon’s extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

9

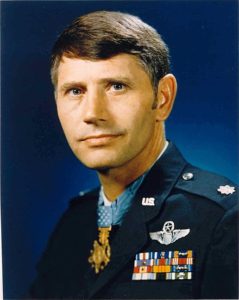

On April 19, 1967, Major Thorsness and his Electronic Warfare Officer, Captain Harold E. Johnson led flight team (Kingfish) on a missionagainst an enemy army training compound, near Hanoi. Thorsness directed 2 of his team to troll north while he and his wingman maneuvered south, forcing defending gunners to divide their attention. Thorsness located two SAM sites and took them out.

The Kingfish 02 was hit by anti-aircraft fire and both crewmen had to eject. Kingfish 03 and 04 had been attacked by MiG-17s and disengaged to return to base, leaving Kingfish 01 to fight solo.

As Thrsness circled the parachutes of Kingfish 02 crew, Johnson spotted a MiG-17 off their right wing. Thorsness, even though his F-105 was not designed for air-to-air combat, attacked the MiG and destroyed it with 20-mm cannon fire, just as a second MiG closed on his tail. Low on fuel, Thorsness outran his pursuers and left the battle area to rendezvous with a KC-135 tanker over Laos.

As this occurred, Search and Rescue arrived to locate the position of the downed crewmen before calling in the rescue helicopters. Thorsness, with only 500 rounds of ammunition left, turned back from the tanker to fly rescue combat air patrol for the S&R and update them on the situation and terrain. As Thorsness approached the area, he spotted MiG-17s and attacked, destroying one.

Pairs of MiGs attacked the S&R aircraft, shooting down the leader. S&R 02 reported the situation and Thorsness advised him to keep evading and announced his return.

Although all of his ammunition had been depleted, Thorsness reversed and flew back to the scene, hoping in some way to draw the MiGs away. However, as he re-engaged, a 2nd flight team (Panda) arrived back in the area. Panda’s four F-105s burst through the defensive circle at high speed, then engaged the MiGs in a turning dogfight, permitting Kingfish 01 to depart the area after a 50-minute engagement against SAMs, antiaircraft guns, and MiGs.

Again low on fuel and facing nightfall, Thorsness was headed towards a tanker when Panda 03 transmitted by radio that he was critically low on fuel. Thorsness quickly calculated that Kingfish 01 had sufficient fuel to fly to Udorn, near the Mekong River and 200 miles closer, so he vectored the tanker toward Panda 03. When within 60 miles of Udorn, he throttled back to idle and “glided” toward the base, touching down “long” (mid-runway) as his fuel totalizer indicated empty tanks. Johnson told Thorsness upon touchdown, “Leo, that was a full day’s work.”

On April 19, 1967, Major Thorsness and his Electronic Warfare Officer, Captain Harold E. Johnson led flight team (Kingfish) on a missionagainst an enemy army training compound, near Hanoi. Thorsness directed 2 of his team to troll north while he and his wingman maneuvered south, forcing defending gunners to divide their attention. Thorsness located two SAM sites and took them out.

The Kingfish 02 was hit by anti-aircraft fire and both crewmen had to eject. Kingfish 03 and 04 had been attacked by MiG-17s and disengaged to return to base, leaving Kingfish 01 to fight solo.

As Thrsness circled the parachutes of Kingfish 02 crew, Johnson spotted a MiG-17 off their right wing. Thorsness, even though his F-105 was not designed for air-to-air combat, attacked the MiG and destroyed it with 20-mm cannon fire, just as a second MiG closed on his tail. Low on fuel, Thorsness outran his pursuers and left the battle area to rendezvous with a KC-135 tanker over Laos.

As this occurred, Search and Rescue arrived to locate the position of the downed crewmen before calling in the rescue helicopters. Thorsness, with only 500 rounds of ammunition left, turned back from the tanker to fly rescue combat air patrol for the S&R and update them on the situation and terrain. As Thorsness approached the area, he spotted MiG-17s and attacked, destroying one.

Pairs of MiGs attacked the S&R aircraft, shooting down the leader. S&R 02 reported the situation and Thorsness advised him to keep evading and announced his return.

Although all of his ammunition had been depleted, Thorsness reversed and flew back to the scene, hoping in some way to draw the MiGs away. However, as he re-engaged, a 2nd flight team (Panda) arrived back in the area. Panda’s four F-105s burst through the defensive circle at high speed, then engaged the MiGs in a turning dogfight, permitting Kingfish 01 to depart the area after a 50-minute engagement against SAMs, antiaircraft guns, and MiGs.

Again low on fuel and facing nightfall, Thorsness was headed towards a tanker when Panda 03 transmitted by radio that he was critically low on fuel. Thorsness quickly calculated that Kingfish 01 had sufficient fuel to fly to Udorn, near the Mekong River and 200 miles closer, so he vectored the tanker toward Panda 03. When within 60 miles of Udorn, he throttled back to idle and “glided” toward the base, touching down “long” (mid-runway) as his fuel totalizer indicated empty tanks. Johnson told Thorsness upon touchdown, “Leo, that was a full day’s work.”10

Jay Zeamer Jr. was a pilot of the United States Army Air Forces in the South Pacific during World War II, who received the Medal of Honor for valor during a B-17 Flying Fortress mission on June 16, 1943.

Arriving too early at Bougainville to start an aerial mapping mission, Zeamer opted to recon a nearby Japanese airstrip at Buka. Zeamer flew northeast in a loop to come back over Buka on their way into the mapping run. With approximately a minute left in the mapping run, “Old 666” faced a coordinated attack by eight Zero fighters. The ensuing attack mortally wounded bombardier Sarnoski, who struggled back to his machine gun to drive off a second Zero after being blown back from his position by a 20 mm cannon shell from the first Zero. A total of four 20 mm shells destroyed the pilot’s side of the instrument panel and broke Zeamer’s left leg above and below the knee, leaving a large hole in his left thigh. He was also hit by shrapnel in both arms and his right leg, with a gash in his right wrist. Three others were also wounded, including the navigator and top turret gunner, who responded to a resulting oxygen fire by putting it out with rags and their bare hands.

Due to the loss of oxygen and to escape their attackers, Zeamer dived the B-17 violently from 25,000 feet to approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 m). The Japanese followed them down and commenced a forty-minute series of attack passes at the nose of the B-17. Despite his wounds, Zeamer avoided any further extensive damage to the plane by repeatedly turning into the oncoming fighters, just inside the trajectory of their fixed fire. By doing so, the Zeros would continue rolling into the bomber without hitting it, but exposing themselves to the B-17’s rear machine guns. Eventually, all of the Zeros broke off the attack due either to damage, lack of ammunition, or lack of fuel.

After the engagement, an assessment revealed that the B-17’s oxygen and hydraulic systems were destroyed, as well as all of the pilot’s flight instruments. The magnetic compass and engine instruments on the co-pilot’s side were undamaged, as were all four engines. Too wounded to move and unwilling to give up command of his aircraft, Zeamer advised the top turret gunner after he took over co-piloting duties, allowing the unwounded co-pilot to attend to the wounded. The lack of oxygen, in addition to Zeamer’s and the navigator’s injuries, meant a return to Port Moresby over the Owen Stanley Mountains was impossible. Instead, they made an emergency landing at an Allied fighter airstrip at Dobodura, New Guinea. Without operable brakes or flaps because of the destroyed hydraulic system, the B-17 was ground-looped, without additional damage, by the co-pilot. The casualties were one killed (Sarnoski) and four wounded. Zeamer was initially thought dead from loss of blood, but he was treated with the other injured aircrew members by the 10th Field Ambulance of the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps before being transported back to Port Moresby the next day.

Jay Zeamer Jr. was a pilot of the United States Army Air Forces in the South Pacific during World War II, who received the Medal of Honor for valor during a B-17 Flying Fortress mission on June 16, 1943.

Arriving too early at Bougainville to start an aerial mapping mission, Zeamer opted to recon a nearby Japanese airstrip at Buka. Zeamer flew northeast in a loop to come back over Buka on their way into the mapping run. With approximately a minute left in the mapping run, “Old 666” faced a coordinated attack by eight Zero fighters. The ensuing attack mortally wounded bombardier Sarnoski, who struggled back to his machine gun to drive off a second Zero after being blown back from his position by a 20 mm cannon shell from the first Zero. A total of four 20 mm shells destroyed the pilot’s side of the instrument panel and broke Zeamer’s left leg above and below the knee, leaving a large hole in his left thigh. He was also hit by shrapnel in both arms and his right leg, with a gash in his right wrist. Three others were also wounded, including the navigator and top turret gunner, who responded to a resulting oxygen fire by putting it out with rags and their bare hands.

Due to the loss of oxygen and to escape their attackers, Zeamer dived the B-17 violently from 25,000 feet to approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 m). The Japanese followed them down and commenced a forty-minute series of attack passes at the nose of the B-17. Despite his wounds, Zeamer avoided any further extensive damage to the plane by repeatedly turning into the oncoming fighters, just inside the trajectory of their fixed fire. By doing so, the Zeros would continue rolling into the bomber without hitting it, but exposing themselves to the B-17’s rear machine guns. Eventually, all of the Zeros broke off the attack due either to damage, lack of ammunition, or lack of fuel.

After the engagement, an assessment revealed that the B-17’s oxygen and hydraulic systems were destroyed, as well as all of the pilot’s flight instruments. The magnetic compass and engine instruments on the co-pilot’s side were undamaged, as were all four engines. Too wounded to move and unwilling to give up command of his aircraft, Zeamer advised the top turret gunner after he took over co-piloting duties, allowing the unwounded co-pilot to attend to the wounded. The lack of oxygen, in addition to Zeamer’s and the navigator’s injuries, meant a return to Port Moresby over the Owen Stanley Mountains was impossible. Instead, they made an emergency landing at an Allied fighter airstrip at Dobodura, New Guinea. Without operable brakes or flaps because of the destroyed hydraulic system, the B-17 was ground-looped, without additional damage, by the co-pilot. The casualties were one killed (Sarnoski) and four wounded. Zeamer was initially thought dead from loss of blood, but he was treated with the other injured aircrew members by the 10th Field Ambulance of the Royal Australian Army Medical Corps before being transported back to Port Moresby the next day.11

Britt Kelly Slabinski is a retired United States Navy SEAL who received the Medal of Honor on May 24, 2018, for his actions during the Battle of Takur Ghar. He also participated in the highly publicized rescue mission to recover Army PFC Jessica Lynch.

Britt Kelly Slabinski is a retired United States Navy SEAL who received the Medal of Honor on May 24, 2018, for his actions during the Battle of Takur Ghar. He also participated in the highly publicized rescue mission to recover Army PFC Jessica Lynch.

For Services as Set Forth in the Following

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while assigned to a Joint Task Force in support of Operation ENDURING FREEDOM. In the early morning of 4 March 2002, Senior Chief Special Warfare Operator Slabinski led a reconnaissance team to its assigned area atop a 10,000-foot snow-covered mountain. Their insertion helicopter was suddenly riddled with rocket-propelled grenades and small arms fire from previously undetected enemy positions. The crippled helicopter lurched violently and ejected one teammate onto the mountain before the pilots were forced to crash land in the valley far below. Senior Chief Slabinski boldly rallied his five remaining team members and marshalled supporting assets for an assault to rescue their stranded teammate. During reinsertion the team came under fire from three directions, and one teammate started moving uphill toward an enemy strongpoint. Without regard for his own safety, Senior Chief Slabinski charged directly toward enemy fire to join his teammate. Together, they fearlessly assaulted and cleared the first bunker they encountered. The enemy then unleashed a hail of machine gun fire from a second hardened position only twenty meters away. Senior Chief Slabinski repeatedly exposed himself to deadly fire to personally engage the second enemy bunker and orient his team’s fires in the furious, close-quarters firefight. Proximity made air support impossible, and after several teammates became casualties, the situation became untenable. Senior Chief Slabinski maneuvered his team to a more defensible position, directed air strikes in very close proximity to his team’s position, and requested reinforcements. As daylight approached, accurate enemy mortar fire forced the team further down the sheer mountainside. Senior Chief Slabinski carried a seriously wounded teammate through deep snow and led a difficult trek across precipitous terrain while calling in fire on the enemy, which was engaging the team from the surrounding ridges. Throughout the next 14 hours, Senior Chief Slabinski stabilized the casualties and continued the fight against the enemy until the hill was secured and his team was extracted. By his undaunted courage, bold initiative, leadership, and devotion to duty, Senior Chief Slabinski reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

12

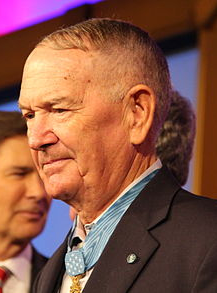

Early on a cold November morning in Korea in 1950, an American soldier left the safety of his position to draw enemy fire away from his fellow Army Rangers.

That soldier, Ralph Puckett Jr., is an Eagle Scout.

“With full knowledge of the danger, 1st Lt. Puckett intentionally ran across an open area three times to draw enemy fire, thereby allowing the Rangers to locate and destroy the enemy positions and to seize Hill 205,” according to the official White House account. “Over the course of the counterattack, the Rangers were inspired and motivated by the extraordinary leadership and courageous example exhibited by 1st Lt. Puckett.”

For his conspicuous gallantry during the Korean War, Puckett has been awarded the Medal of Honor — our country’s most prestigious military award.

Puckett, 94, becomes at least the 12th Eagle Scout to receive the Medal of Honor, joining fellow Eagle Scouts who have demonstrated bravery during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the War in Afghanistan.

In a stroke of humility befitting an Eagle Scout, Puckett’s first reaction upon learning he had received the Medal of Honor was to ask, “Why all the fuss? Can’t they just mail it to me?”

“Col. Puckett, after 70 years, rather than mail it to you I would have walked it to you,” President Joe Biden said during the White House ceremony. “Your lifetime of service to our nation I think deserves a little bit of fuss.”

Early on a cold November morning in Korea in 1950, an American soldier left the safety of his position to draw enemy fire away from his fellow Army Rangers.

That soldier, Ralph Puckett Jr., is an Eagle Scout.

“With full knowledge of the danger, 1st Lt. Puckett intentionally ran across an open area three times to draw enemy fire, thereby allowing the Rangers to locate and destroy the enemy positions and to seize Hill 205,” according to the official White House account. “Over the course of the counterattack, the Rangers were inspired and motivated by the extraordinary leadership and courageous example exhibited by 1st Lt. Puckett.”

For his conspicuous gallantry during the Korean War, Puckett has been awarded the Medal of Honor — our country’s most prestigious military award.

Puckett, 94, becomes at least the 12th Eagle Scout to receive the Medal of Honor, joining fellow Eagle Scouts who have demonstrated bravery during World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War and the War in Afghanistan.

In a stroke of humility befitting an Eagle Scout, Puckett’s first reaction upon learning he had received the Medal of Honor was to ask, “Why all the fuss? Can’t they just mail it to me?”

“Col. Puckett, after 70 years, rather than mail it to you I would have walked it to you,” President Joe Biden said during the White House ceremony. “Your lifetime of service to our nation I think deserves a little bit of fuss.”First heroes of our community, the heroes of our nation.